Most pictures of hydroelectric power showcase the same dramatic elements: a colossal concrete dam, a vast, placid reservoir, and powerful jets of white water. But beyond the sheer scale, these images are a testament to incredible engineering. They capture a story of physics, material science, and environmental planning, all working in concert to convert the simple force of flowing water into clean, reliable electricity for millions.

This deep dive goes beyond the surface to explore the engineering decisions and trade-offs embedded in every hydropower facility. By understanding the core components and design principles, you can learn to “read” these photos like an engineer, seeing the invisible forces at play.

At a Glance: What You’ll Learn

- Deconstruct Dam Designs: Discover why a dam is built as a massive gravity wall, a graceful arch, or a supported buttress structure based on the local geology.

- Follow the Water’s Path: Trace the journey of water from the reservoir intake, through the penstock, into the turbine, and out the tailrace.

- Understand Turbine Technology: Learn how engineers choose between Francis, Kaplan, and Pelton turbines to perfectly match the water’s pressure and flow rate.

- See the Ecological Engineering: Identify features like fish ladders and aeration systems that balance power generation with environmental stewardship.

- Analyze Photos Like an Expert: Gain a practical framework for interpreting pictures of hydroelectric power to understand the specific engineering choices made at any facility.

What a Dam’s Shape Tells You About Its Job

The dam is the most recognizable feature of any large-scale hydropower plant, but its design is anything but arbitrary. The shape, size, and material are dictated by the landscape and the immense force of the water it must contain—known as hydrostatic pressure. Engineers choose from several primary designs, each with unique strengths.

Gravity Dams: The Brute Force Approach

As the name implies, a gravity dam relies on its own colossal weight to resist the push of the water. Made from massive amounts of concrete or masonry, these dams are thick at the base and taper towards the top, creating a stable triangular profile. They are best suited for wide valleys with strong, stable rock foundations capable of supporting their immense load.

When you see a picture of a straight, thick wall of concrete spanning a wide river, you’re likely looking at a gravity dam. The Hoover Dam is a world-famous example, though it incorporates a slight arch for added strength. Its sheer mass is what does the primary work of holding back Lake Mead.

Arch Dams: Engineering Elegance Under Pressure

In narrow, steep-walled canyons, an arch dam is a far more efficient solution. This elegant, curved design acts like a horizontal arch, transferring the water’s pressure outward into the strong rock of the canyon walls. This allows them to be much thinner and use significantly less concrete than a gravity dam of similar height.

However, their stability is entirely dependent on the abutments—the sides of the canyon—being unyieldingly strong. The Kariba Dam on the Zambezi River is a classic arch dam. In a photo, its graceful, convex curve facing the reservoir is the key identifying feature.

Buttress Dams: A Hybrid of Strength and Efficiency

Buttress dams are a clever compromise between gravity and arch designs. They consist of a relatively thin, sloping upstream wall that is supported by a series of massive buttresses on the downstream side. The buttresses redirect the water’s force down into the foundation.

This design requires less concrete than a gravity dam but more complex formwork during construction. They are often used in wide valleys where the foundation rock is solid but saving on materials is a priority. Pictures will clearly show these repeating, triangular supports on the “dry” side of the dam.

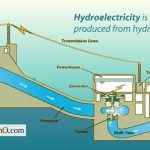

The Water’s Journey: From Reservoir to River

Every hydropower plant, regardless of size, is engineered to guide water through a specific sequence of components to extract its energy. Understanding this path is crucial to appreciating how the entire system functions. To see these components in action across different facilities, you can View water power photos and try to identify each part of the system.

Here’s a breakdown of the key stages:

| Component | Engineering Purpose | What to Spot in a Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Reservoir | Stores water, creating “head”-the height difference that builds potential energy. | The large body of water held behind the dam. |

| Intake & Trash Rack | The entry point for water into the system. A trash rack (a large grate) filters out debris like logs and ice. | Gated, submerged structures often visible on the upstream face of the dam. |

| Penstock | A large pipe or tunnel that funnels water from the intake down to the turbine. It’s designed to maintain high pressure. | Often hidden within the dam or tunneled through rock, but sometimes visible as massive pipes running down a hillside. |

| Turbine | A machine with blades or buckets that is spun by the force of the moving water, converting the water’s kinetic energy into rotational mechanical energy. | Located inside the powerhouse, usually not visible externally. |

| Generator | Connected to the turbine by a shaft. As the turbine spins, it turns the generator’s rotor within a stator to produce electricity. | Also housed inside the powerhouse, directly above the turbine. |

| Spillway | A safety feature designed to release excess water from the reservoir during floods or high-flow events, preventing the dam from overtopping. | Large gates or a concrete channel on the dam’s crest, often with dramatic plumes of water rushing through them. |

| Tailrace | A channel that carries the water away from the turbine and back into the river downstream. | The area of water flowing out from the base of the powerhouse. |

The Heart of the Machine: Matching Turbine Design to Water Pressure and Flow

The turbine is where the magic happens, and engineers spend countless hours selecting and designing the perfect type for a given site. The choice depends almost entirely on two factors:

- Head: The vertical distance the water falls. High head means high pressure.

- Flow Rate: The volume of water moving through the system over time.

Francis Turbines: The Versatile Workhorse

The Francis turbine is the most widely used design in the world. It looks like a complex, spinning wheel with curved blades. Water enters radially (from the side) and exits axially (downward), creating a highly efficient spin.

- Best For: Medium-head and high-flow situations.

- Real-World Example: The Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River uses massive Francis turbines. They are perfectly suited for the dam’s significant head and the river’s enormous, consistent flow. In pictures of hydroelectric power plant interiors, this is the most common turbine type you’ll see during maintenance.

Kaplan Turbines: The Propeller for Low-Head Power

For sites with a low head but a very high volume of water—like a large, slow-moving river—the Kaplan turbine is ideal. It looks much like a ship’s propeller, and its blades can be adjusted in real-time to optimize efficiency as the flow rate changes.

- Best For: Low-head and very high-flow conditions.

- Real-World Example: A run-of-the-river plant, which generates power without a large reservoir, would use Kaplan turbines. They can efficiently extract energy from the river’s natural flow without needing the immense pressure created by a tall dam.

Pelton Wheels: The Master of High-Pressure Jets

In mountainous regions with extremely high head but relatively low flow, the Pelton wheel reigns supreme. This design is an “impulse” turbine. It doesn’t sit submerged in the water; instead, high-pressure jets of water are fired at a series of spoon-shaped buckets arranged around a wheel, spinning it at high speed.

- Best For: Very high-head and low-flow environments.

- Real-World Example: Hydropower plants in the Swiss Alps or Norway’s fjords use Pelton wheels. They harness the incredible pressure generated by water piped down from a reservoir thousands of feet up a mountain.

Beyond Concrete and Steel: Engineering for the Environment

Modern hydropower engineering is about more than just maximizing megawatt output. A significant amount of design and planning is dedicated to mitigating the facility’s impact on the local ecosystem. These features are often visible in detailed pictures of hydroelectric power facilities.

Fish Ladders and Lifts: A Path for Migration

One of the primary ecological challenges of dams is that they block the natural migration paths of fish like salmon and trout. To solve this, engineers design “fishways.” The most common is the fish ladder, a series of small, cascading pools that allow fish to “climb” past the dam. In some high-head dams, a fish lift—essentially an elevator for fish—is used instead.

Turbine Aeration and Dissolved Oxygen

Water released from the bottom of a deep reservoir is often cold and low in dissolved oxygen, which can harm downstream aquatic life. Engineers have developed several solutions, including aerating turbines that are designed to mix air into the water as it passes through. They may also use multi-level intakes that allow them to draw water from different depths to manage the temperature and oxygen content of the water being released.

Sediment Management

Rivers naturally carry sediment downstream. A dam traps this sediment, which can slowly fill the reservoir and rob downstream habitats of essential nutrients. Engineers now incorporate strategies like sediment flushing, where special gates are opened to scour out accumulated silt, or sediment bypass tunnels that route sediment-heavy water around the dam during high-flow events.

A Field Guide to Analyzing Hydropower Photos

With this engineering knowledge, you can analyze pictures of hydroelectric power plants with a new perspective. Use this checklist to decode what you’re seeing:

- Identify the Dam Type: Is it a massive, straight gravity dam, a graceful arch, or a buttress-supported structure? This tells you about the geology of the site—wide valley vs. narrow canyon.

- Estimate the ‘Head’: Look at the height difference between the reservoir and the tailrace. A towering wall in the mountains implies a high-head site (likely a Pelton wheel). A long, low dam across a wide river is a low-head site (likely Kaplan turbines).

- Spot the Spillway: Is it active and releasing water? This indicates the reservoir is full, possibly due to recent heavy rains or spring snowmelt. The spillway’s capacity is a critical part of the dam’s safety engineering.

- Locate the Powerhouse: Is it a separate building at the foot of the dam or integrated into the structure itself (an “integral powerhouse”)? Its size gives you a rough idea of the plant’s generating capacity.

- Look for Environmental Features: Can you spot the zig-zagging structure of a fish ladder on the side of the dam? Do you see multiple outlet points on the dam’s face, suggesting a system for managing water temperature? These details reveal a focus on modern, sustainable engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions About Hydropower Engineering

Q: Why can’t we put a hydroelectric plant on any river?

A: Effective power generation requires both sufficient water flow (volume) and a significant head (vertical drop). A flat, slow-moving river may have plenty of flow, but without the head to create water pressure, it lacks the concentrated potential energy needed to spin a turbine efficiently. The site also needs a suitable geological foundation to support a dam.

Q: Are smaller, “micro-hydro” systems engineered differently?

A: The core principles are identical, but the scale and implementation differ. Micro-hydro systems often use a “run-of-the-river” design that doesn’t require a large dam or reservoir. Instead, a small weir diverts a portion of the river’s flow into a penstock. The engineering challenge is to generate meaningful power with minimal disruption to the river’s natural state.

Q: What is “pumped-storage” hydropower?

A: Pumped-storage is an ingenious energy storage method that acts like a giant, water-based battery. These facilities have both an upper and a lower reservoir. During periods of low electricity demand (e.g., at night), they use cheap power from the grid to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper one. During peak demand, they release that water back down through turbines to generate electricity, selling it back to the grid at a higher price. It’s one of the most efficient, large-scale energy storage solutions available today.

From a Single Image to a System-Wide View

A photograph of a hydroelectric dam is more than just a picture of a large structure; it’s a snapshot of a complex, dynamic system. It represents a balancing act between raw power and environmental responsibility, between brute-force physics and elegant design. By looking for the clues—the shape of the dam, the height of the water, the presence of a spillway or fish ladder—you can begin to understand the immense engineering challenges that were solved to bring it to life.

The next time you encounter a picture of a hydroelectric facility, look past the monumental scale. See the careful calculations, the material science, and the ecological considerations. You’ll be reading the hidden language of engineering that turns a simple river’s flow into a cornerstone of sustainable energy.

- Is Hydropower Renewable Or Nonrenewable Resource? Sorting Out the Facts - March 3, 2026

- Hydroelectric Power Basics How Water Is Used For Electricity - February 26, 2026

- Portable Water Generators Power Off-Grid Homes and Adventures - February 25, 2026